Tchaikovsky and the Triad – Part 6

Yes, believe it or not, we’re still talking about triads. We’re almost done though. Maybe one or two more posts. Triads are the basic building blocks of Western diatonic harmony, so it makes sense that we’d be spending a considerable amount of time on them.

In the last post we discussed how common tones between triads can be used to progress from one unique triad or chord to another. While this is probably the easiest and most logical way to move between triads, there are certainly other ways of doing so. Let’s take a look!

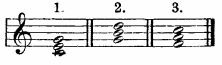

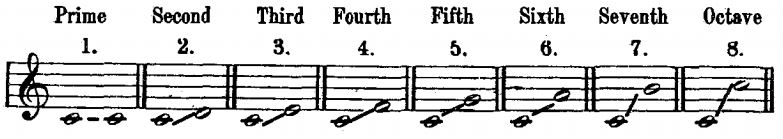

There are several ways we can move from one triad to another. One such way is called parallel motion, or the movement of two tones in the same direction–upwards or downwards:

One can also move in oblique motion, in which one tone stays the same while the other voice moves upwards or downwards. This is the motion typically used when a common tone is maintained:

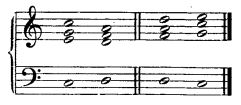

And finally we have contrary motion, where both voices move in opposite directions–one moves up, the other moves down:

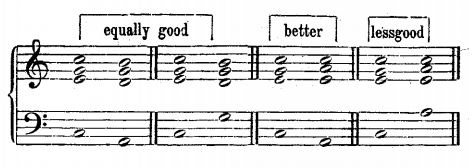

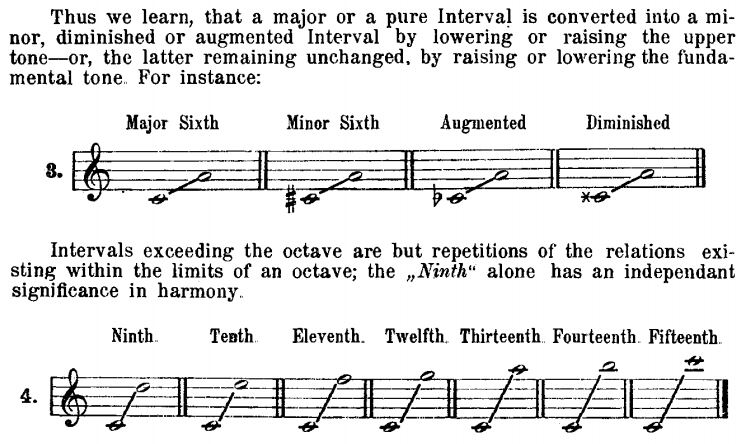

Now, if you think you can move tones willy-nilly using any one of the above motions, think again. Moving tones correctly can be especially difficult when dealing with parallel motion. Tchaikovsky states that moving tones in parallel motion by second or fourth intervals is allowable, just so long as both tones move by the same interval (ignore the third bar in the example because it’s bad–you’ll soon find out why):

The thing that must be absolutely avoided is moving from a fifth or octave into another fifth or octave using parallel motion:

Wait, but why? What’s so wrong with this kind of motion? Well, for one, it just sounds terrible when dealing with sparse four-part harmonic writing. Or if you want the long answer, here’s what Prof. T has to say about parallel fifths and octaves:

Ugh, so many rules, right?? Well, this is just the tip of the iceberg, friends. Don’t get discouraged–let’s keep going!

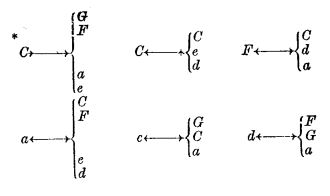

So, we want to move from one chord to another without using a common tone. Hmm, how should we approach this. Well, I guess we could move all the tones of the chord up or down by a second interval. Would that work?

Oopsy! Extra credit to anyone who can tell me what’s wrong here! So many things wrong…First of all, we have both an octave AND a fifth moving in parallel motion. For shame! This won’t do at all. So how about this?

Ahh, this is much better. My ears have finally stopped screaming. Now this is what a chord progression is supposed to look like. The best way to avoid those nasty parallel octaves and fifths is just to simply move tones in contrary motion, as you can see above.

Instead of moving the tonic C up by a second interval, you can avoid parallel fifths and octaves while still moving to the same new chord (D minor) by lowering the tonic by the interval of a seventh to the D below. But is this really the best solution? Remember, basses don’t like those big jumps! Very unmelodious, as Tchaikovsky puts it.

So how about this?

And there we have it: the most correct answer. Isn’t that a beautiful sight to behold? I’m sure it sounds even better! In this example, not only do we avoid those terrible parallels, but we also give the bass a nice and relaxing second interval to sing. See how things change yet still remain essentially the same? Welcome to the wonders of harmony!

One thing to remember when working with four-part harmony is that contrary motion is your best friend. Sure the other motions are useful, but none quite so commonly used as contrary motion–take it from me, it’ll save your life some day!

Important Stuff:

- Parallel motion – the movement of two tone upwards or downwards in the same direction.

- Oblique motion – one tone moves upward or downward while the second tone stays put.

- Contrary motion – the movement of two tones in opposite directions–one moves up, the other moves down.